Atari Mindlink

Before Neuralink, There Was This

In the early 1980s, Atari was everywhere. They made the Atari 2600, which brought video games into millions of homes. By then, they weren’t just a game company—they were the game company. But Atari wanted more. They wanted to do something no one had done before.

They wanted you to play games with your mind.

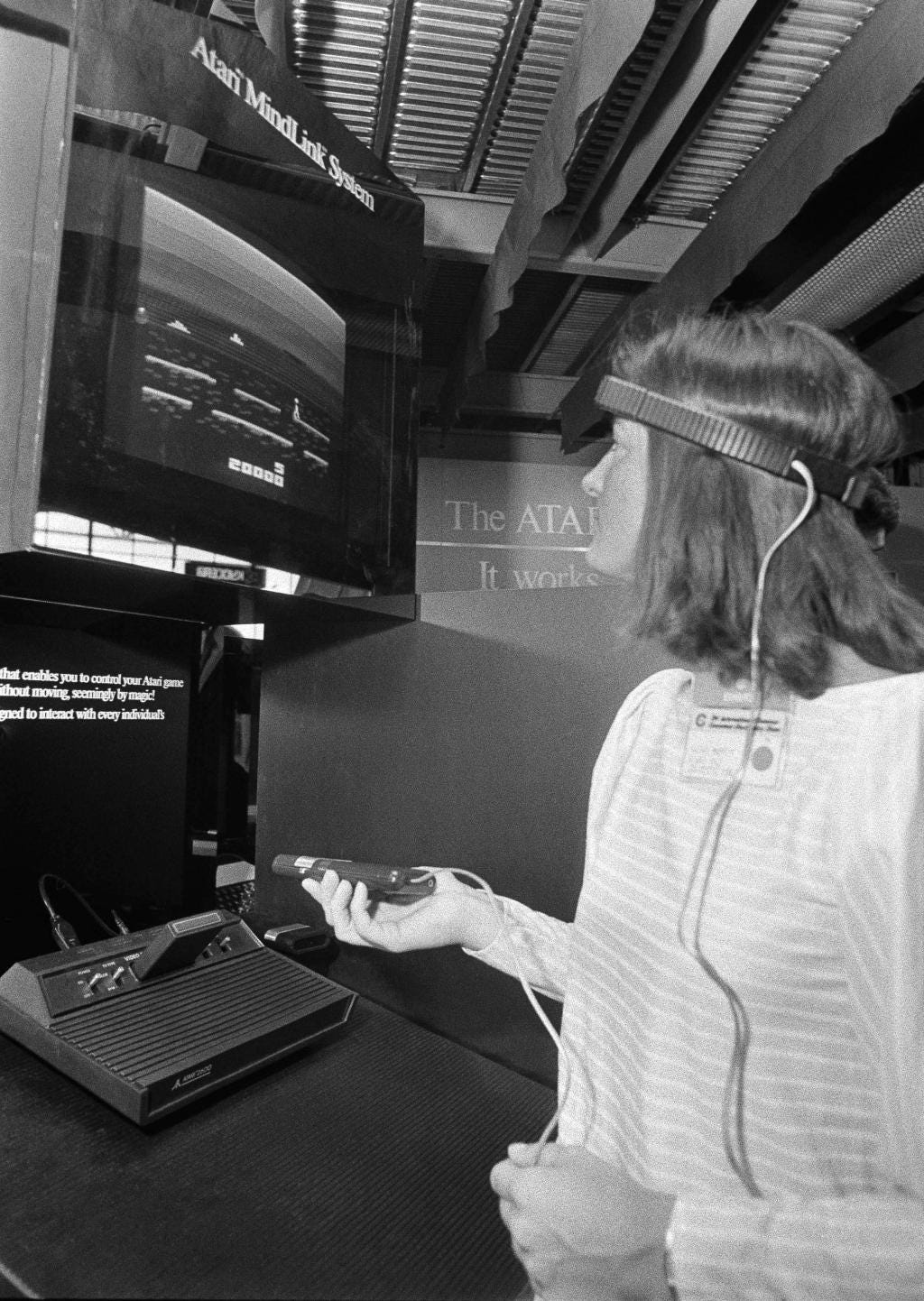

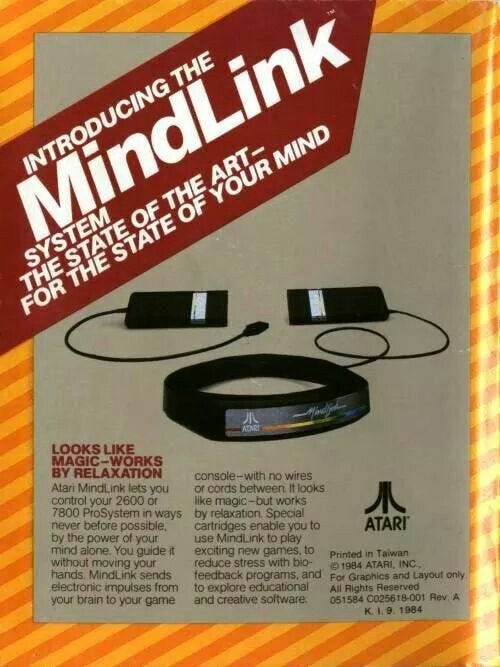

That was the pitch behind the Atari Mindlink. It looked like a plastic headband. You wore it across your forehead like a sweatband from a sci-fi gym. It didn’t actually read your thoughts—but that’s what the marketing hinted at. What it did read were the small electrical signals in your forehead muscles, picked up through sensors. So when you tensed or moved your eyebrows, those signals triggered controls in the game.

That was the theory.

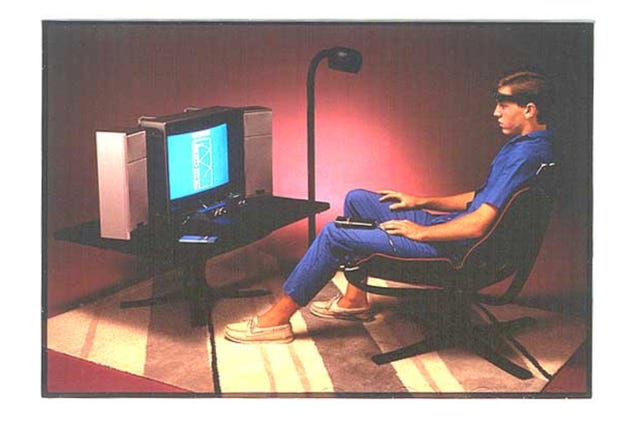

The Mindlink was designed for the Atari 2600. It would have connected through the standard joystick port. The idea was to give players a “hands-free” gaming experience, something nobody had tried before. You could sit still, raise one eyebrow slightly, and control what was happening on screen.

In 1984, Atari showed off the Mindlink at the Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago. They had built three games for it.

The first was Bionic Breakthrough. It was like Breakout, but instead of moving a paddle with a joystick, you did it with your eyebrows. You could tilt the paddle left or right by flexing your muscles a certain way.

The second was Telepathy. It was a basic “psychic training” game. Shapes or symbols would appear on screen, and you had to match or anticipate them. The controls were still eyebrow-based, but it was wrapped in a theme of mind-reading.

The third was Mind Maze, a simple logic puzzle game. It used headband input to select answers or navigate menus.

They were never released.

The hardware didn’t work as well as it needed to. For most people, it was hard to control. You had to learn which muscles to move, and even then, it wasn’t precise. Testing showed that people got headaches from using it for too long. The forehead sensors needed constant, careful placement. And the results weren’t consistent. If the band shifted even a little, the game might stop responding.

The idea sounded futuristic, but the tech wasn’t ready.

And the timing couldn’t have been worse.

In 1983, the video game market crashed. Atari, once worth billions, started losing money fast. Too many bad games. Too many rushed products. Confidence in the market dropped. Shelves were full of unsold cartridges. And parents who bought consoles just months earlier weren’t buying more.

Then came Jack Tramiel.

In 1984, Warner sold Atari’s home division to Tramiel, the founder of Commodore. He had made the Commodore 64 and was focused on computers, not risky side projects. When he came in, he cut costs fast. Anything that wasn’t essential got scrapped. The Mindlink was one of the first things to go.

Atari never made a formal announcement. The Mindlink wasn’t canceled in public—it just vanished. No games were released for it. No final version was produced. And very few prototypes survived.

Only a handful of units are known to exist. One is held by the National Videogame Museum in Texas. Another has surfaced in online collector circles. They don’t work well today, and most of the games built for it are lost or incomplete.

Despite all that, the Mindlink has become a strange kind of legend.

Not because it worked.

But because it dared to ask: what if we didn’t need hands at all?

In a way, it predicted something important. Today, we have brain-computer interfaces that do exactly what the Mindlink pretended to do. Elon Musk’s Neuralink isn’t a game controller, but it does let people move cursors or type using brain signals. Medical companies now develop headsets that let people with paralysis control devices just by thinking.

The Mindlink didn’t invent any of that. But it imagined the future—before the technology caught up.

There’s also another angle to this story: marketing.

The Mindlink may not have worked, but the ads almost convinced you it did. Atari was going to market it like a new frontier of gaming. “Play with your mind.” Simple slogans. Big ideas. No real explanation.

There were no YouTube reviews. No early access. No Reddit threads tearing it down. Just printed ads and magazine spreads with dramatic photos and short promises.

That’s how it used to be.

And somehow, it felt more exciting.

The Mindlink never made it to store shelves. But it left a strange legacy.

It’s one of the first times a company tried to change how we interact with games in a big way. It failed. But that’s what happens when you try something new.

Most people don’t talk about it now. You won’t find it on top 10 lists or gaming retrospectives. But it was there—for a moment—pointing toward a future that, slowly, is starting to happen.

This is what I love about taking a look back at retro games. Just when I think I’ve seen it all, there’s always something I’ve never heard of (usually a peripheral of some sort). Thanks for making me aware of this.